Battle of Bosworth Field

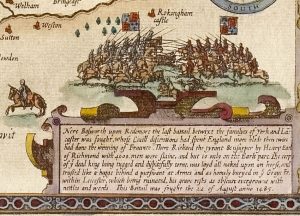

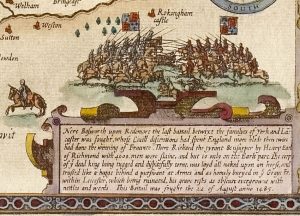

The Battle of Bosworth Field took place on 22nd August 1485. Supporters of King Richard III fought against the army of Henry Tudor. The Stanley’s joined the battle as it was fought. Richard III led an attack aimed at slaying Henry Tudor. Richard’s assault failed and he himself was killed. Henry Tudor was proclaimed king as a result of his victory at Bosworth. Victory in the battle did not end the Wars of the Roses. The remains of Richard III were taken to Leicester where he was buried with little ceremony. His body has since been discovered by Archaeologists from the University of Leicester. His reinterment took place at Leicester Cathedral in 2015.

.

Why did Henry Tudor invade in 1485?

Henry Tudor became the figurehead for Lancastrian support following the defeats at Barnet and Tewkesbury. Though in exile, he was able to gain support from families who had lost out as a result of those Yorkist victories. As the head of the line, his only real hope of acquiring the lands that his family lost after 1471 was through use of force. That in itself meant that he would have to take up the Lancastrian claim to the throne. Henry’s claim was quite tenuous. It came through a second marriage and so wasn’t the line of succession to which we, or the people of the 15th century, were accustomed to. However, by 1485 the political situation in England had changed to the extent that an invasion seemed viable. Indeed, it had been planned to take place earlier. Henry’s invasion was possible in 1485 because of the level of discontent in England. Rebellion against Richard III had occurred across much of the South of England. With Richard having to deal with uprisings, it was a good time to gain support for a rival claim and also an opportunity to exploit the unrest. 1485 was also significant as Richard’s son and heir had died in 1484. This meant that even if Richard were to have more children it would be some years before they would be old enough to rule. Another child monarch was something that people wanted to avoid.

How was Henry Tudor able to get support for his cause?

Support for Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, came from several sources. His ancestral lands and those of his kin were supportive of his claim. His invasion force landed in South Wales to make the most of these supporters. The Buckingham rebellion saw many nobles and those of the gentry begin to look for a viable alternative to Richard. With Edward V presumed dead, Henry was the next best thing. Support also came from overseas. Funding for the expedition was possible because of the foreign interest in English affairs. This allowed mercenaries to be hired for the invasion of England. Nobles who were likely to benefit from the accession of a rival claim were willing to take a risk in supporting Tudor’s campaign.

Henry also offered the prospect of lasting peace. He intended to marry Elizabeth of York. This marriage would have political benefits. Uniting the different lines of the Plantagenet house prevents alternative claims: apart from any purporting to be the Princes in the Tower.

Was Richard III prepared for an invasion?

Henry, Earl of Richmond, had been close to landing an invasion force during Buckingham’s rebellion. He had a force off the shore of Plymouth but did not make landfall and returned to France. The intention to land had been known to Richard and the royal household. In short, an invasion by Henry was expected. With that in mind a general state of readiness was put into place. On 11th August when Richard heard of Tudor’s landing, he summoned these men to join him. He was based in Nottingham and could draw upon estates loyal to him in the midlands and north. He appears to have misjudged the willingness of some nobles to support him though.

Henry Tudor’s invasion

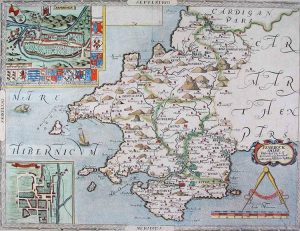

Henry sailed from France to Milford Haven in Pembrokeshire. From here, deep in sympathetic lands, he marched north east through Wales. On the way he gathered additional troops. The force made it’s way to Shrewsbury where it was joined by other nobles who supported Henry’s claim. From here, it made it’s way into the Midlands.

The Battlefield: location, topography and battle formations

Bosworth Field is the plain underneath Ambion Hill near Sutton Cheney in Leicestershire. It was here that the fighting took place. Richard and his force had begun the day camped on Ambion Hill. The Stanley contingent watched from nearby Dadlington Hill.

Richard’s army was larger than that of Henry. He drew up his force in 3 groups. One commanded by himself, the other two under the leadership of the Duke of Norfolk and Earl of Northumberland respectively. They were positioned on Ambion Hill.

Henry placed most of his force under the command of the Earl of Oxford, an experienced commander. Some 1800 troops are believed to have been French mercenaries under the command of Philbert de Chandee. All of Henry’s army formed up on the plain beneath Ambion Hill.

The course of the Battle of Bosworth

The opening of the battle saw Oxford decide to move his men to firmer ground. He wanted to keep them in one formation to prevent small groups being overwhelmed by Richard’s larger army. As they did this Richard’s cannon harassed them. The two sides closed for battle with Henry’s men advancing up the hill and the Duke of Norfolk’s men leading the Yorkist advance. Archers loosed thousands of arrows from both sides as they closed in. The hand to hand battle saw the single command structure that Oxford had put into place begin to dominate Norfolk’s men. Richard waved Northumberland forward to sway the battle in his favour.

It is at this point that one of the key turning points of the battle took place. Northumberland did not react. He simply did not lead his men into the fight. This left Norfolk’s men outnumbered as the division of the Yorkist army meant that manoeuvrability was required to make the overall numerical advantage count. Now, there was a threat of the command being overwhelmed. Richard had to react.

Richard led a charge toward Henry. If Henry could be killed, the battle was won. As Richard’s men charged, Stanley joined the battle. It had been unclear which side he would join but now he sided with Henry. This left Richard’s force quite vulnerable. Edward Hall, writing in the 16th century, summarises what he believed happened next:

The vanguard of King Richard, which was put to flight, was picked off by Lord Stanley who with all of 20,000 combatants came at a good place to the aid of the earl. The earl of Northumberland, who was on the king’s side with 10,000 men, ought to have charged the French, but did nothing except to flee, both he and his company, to abandon his King RIchard, for he had an undertaking with the earl of Richmond, as had some others who deserted him in his need. The king bore himself valiantly according to his destiny, and wore the crown on his head; but when he saw this discomforture and found himself alone on the field he thought to run after the others. His horse leapt into a march from which it could not retrieve itself. One of the Welshmen then came after him, and struck him dead with a halberd, and another took his body and put it before him on his horse and carried it, hair hanging as one would bear a sheep.

‘And so he who miserably killed numerous people, ended his days iniquitously and filthily in the dirt and mire, and he who had despoiled churches was displayed to the people naked and without any clothing, and without any royal solemnity was buried at the entrance to a village church.

‘The vanguard [or in one text ‘rearguard’] which the grand chamberlain of England led, seeing Richard dead, turned in flight; and there were in this battle only 300 slain on either side.’

Edward Hall, The Union of the Two Noble Families of Lancaster and York. 1550 (Google Books)

The role of personal feuds in the Battle of Bosworth

Historian Chris Skidmore, writing on the Tudortimes website, notes the significance of Personal feuds in the Battle of Bosworth. Feuds helped to determine which side the nobility would take. The Stanley’s had a long standing feud with the Harrington family. If the opportunity arose, they could benefit from the battle. In this case Thomas Stanley is rewarded in several ways. For his act of joining the battle on Henry’s side, he received the Earldom of Derby and was soon after made Constable of England. His personal feud saw Harrington attained by Henry. Skidmore cites other examples: Blount-Babington; Troutebeck who had property confiscated by Edward IV; Hassalle, who had been put out of office by Richard III; Robert Harcourt who’s father had been attained, joined Henry in exile and many others who had family reasons, often through attainders, to join with the Tudor cause.

The outcome: Richard III’s death

The Rous Rolls provide us with a near contemporary account of the death of Richard III. John Rous had previously written positively about the Yorkist cause. Following Bosworth his writing becomes quite Lancastrian in tone. For Richard, however, he reserves a last positive appraisal:

For in the thick of the fight, and not in the act of flight, King Richard fell in the field, struck by many mortal wounds, as a bold and most valiant prince.

John Rous. Historia Johannis Rossi Warwicensis de Regibus Anglie. BL Record.

Popular legend has Richard III fighting his last on his own. A brave but doomed charge, followed by losing his horse. It lent itself to Shakepeare’s famous lines and pervades to this day. Why? One of the better known Tudor accounts of the Battle of Bosworth deals with Richard’s final acts.

The vanguard of King Richard, which was put to flight, was picked off by Lord Stanley who with all of 20,000 combatants came at a good place to the aid of the earl. The earl of Northumberland, who was on the king’s side with 10,000 men, ought to have charged the French, but did nothing except to flee, both he and his company, to abandon his King RIchard, for he had an undertaking with the earl of Richmond, as had some others who deserted him in his need. The king bore himself valiantly according to his destiny, and wore the crown on his head; but when he saw this discomforture and found himself alone on the field he thought to run after the others. His horse leapt into a march from which it could not retrieve itself. One of the Welshmen then came after him, and struck him dead with a halberd, and another took his body and put it before him on his horse and carried it, hair hanging as one would bear a sheep.

John Major. c1550 A History of Britain.

And moreover, the king ascertaineth you that Richard duke of Gloucester, late called King Richard, was slain at a place called Sandeford, within the shire of Leicester, and brought dead off the field unto the town of Leicester, and there was laid openly, that every man might see and look upon him. And also there was slain upon the same field, John late duke of Norfolk, John late earl of Lincoln, Thomas, late earl of Surrey, Francis Viscount Lovell, Sir Walter Devereux, Lord Ferrers, Richard Radcliffe, knight, Robert Brackenbury, knight, with many other knights, squires and gentlemen, of whose souls God have mercy.

Proclamation of Henry Tudor. 22/23 August 1485 (Cited here).

The death of Richard III has become a legend. Shakespeare’s influence has been significant in forming popular beliefs about the way in which Richard died in battle. The evidence suggests that Richard’s death was gruesome. His remains show that he suffered 11 wounds at or near the time of his death. 9 of these were blows to his skull.

The most likely injuries to have caused the king’s death are the two to the inferior aspect of the skull – a large sharp force trauma possibly from a sword or staff weapon, such as a halberd or bill, and a penetrating injury from the tip of an edged weapon.

Richard’s head injuries are consistent with some near-contemporary accounts of the battle, which suggest that Richard abandoned his horse after it became stuck in a mire and was killed while fighting his enemies.

Professor Guy Rutty, University of Leicester.

It is quite likely that Richard had lost his helmet whilst fighting.

Richard’s injuries represent a sustained attack or an attack by several assailants with weapons from the later medieval period.

The wounds to the skull suggest that he was not wearing a helmet, and the absence of defensive wounds on his arms and hands indicate that he was otherwise still armoured at the time of his death.

Professor Sarah Hainsworth, University of Leicester.

Did the Battle of Bosworth end the Wars of the Roses?

The Battle of Bosworth killed Richard III. It led to Henry becoming King Henry VII. It did not bring an immediate end to hostilities though. As many had joined Henry’s cause because of personal feuds, the same was true of Richard’s cause. The death on the Battlefield of Richard didn’t bring those feuds to an end. They still needed to be dealt with. There was also a question mark over Henry’s legitimacy. The possibility of the Princes in the Tower still being alive was slim but it gave some a little hope of a Yorkist revival. To place the battle into the context of the wider conflict, see this infographic on the wars of the roses.

Richard III’s remains: Why were they removed from the battlefield?

Accounts show that Richard’s remains were taken from the battlefield to Leicester. It was typical of the day to lay out in public the remains of senior figures who had been killed in battle. This was a simple and effective way of communicating the fact to the people. It left no doubt in anybody’s mind that Richard was dead.

Misconceptions about the Battle of Bosworth and Wars of the Roses

The Battle of Bosworth is a hugely significant event. Richard III‘s death ended the rule of the House of Plantagenet. In came Henry Tudor and the beginning of the Tudor Age. It’s an event that gets lots of mentions in the media. One that people ‘think’ they know lots about. Yet the press makes mistakes on this, sometimes getting even the basic facts about the Wars of the Roses, it’s participants and its scale wrong. Here we address a few of the misconceptions and mistakes that we’ve seen in the press or online.

Bosworth ended the Wars of the Roses

No it didn’t. Though the Battle of Bosworth resulted in the death of Richard III and Henry Tudor being crowned, it was not the end of the Wars of the Roses. The last battle of the Wars of the Roses was the Battle of Stoke Field. This victory wasn’t even the end of opposition and plotting against the Tudors by Yorkists. Lambert Simnel had been pardoned and given work in the Kings service, another pretender to the throne appeared in the guise of Perkin Warbeck in the 1490’s. There were attempts to restore the House of York by men who were not pretenders. Richard de la Pole was the last of these.

The Yorkists lost the War of the Roses

This is far too simplistic a statement to make. When Richard III became king a series of events followed that led to the circumstances in which the Tudor invasion was viable. Those circumstances were orchestrated by Yorkists as well as Tudors own supporters. The Royal Household of Edward IV had seen their roles and prominence diminished under Richard’s rule. This had led to the Buckingham led rebellion of October 1483. Buckingham and many other rebels had, until this point, been Yorkists. They opposed the way in which Richard was ruling and wanted to replace him with Henry Tudor as king with Elizabeth of York as a potential bride. That is collusion between the two factions. During the Bosworth campaign, most Yorkist nobles simply did not answer the call to arms. Make of that what you will but it’s not as simple as saying one side was entirely defeated.

Richard III’s death ended the house of York

Simply not true. Richard’s brother, George Duke of Clarence had been attained (outlawed) which disinherited his children: they were still from the house of York though. Even if that line is disregarded due to the attainder, there are other Yorkists who remained alive and active after the death of Richard III at Bosworth. John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, is believed by some historians to have been named the heir to Richard III. He was the nephew of Richard and Edward IV. It was Lincoln who organised the rebellion that led to Simnel being ‘crowned’ in Dublin. He was killed at the Battle of Stoke Field. Most significant of the house of York after the death of Richard was Elizabeth of York. As the senior member of this line she had political importance. Henry Tudor married her, a significant factor in bringing the wars to an end.

Bosworth was the biggest battle

Probably not. The number of people who fought in many medieval battle is hard to gauge accurately. Chronicles were prone to exaggerate and records are sparse for lots of the campaigning of the Wars of the Roses. From the sources available estimates range from a total of 12000 to 20000 taking part in the Battle of Bosworth. Not all of these men actually fought though. Percy did not engage his men. The men under Stanley did engage but quite late in the battle. The numbers involved make this a significant battle but it by no means the largest. According to some estimates the Battle of Towton may more killed than even took the field at Bosworth. The Battle of Barnet has estimates that are larger than those at Bosworth, as has the Second Battle of St. Albans. Even lesser known battles such as Stoke Field have similar estimated numbers. The biggest problem here is that the contemporary sources are not consistent, or reliable. Modern studies of Battlefields tend to have much lower estimates than the numbers in any contemporary account.

The Wars of the Roses was thirty years of fighting

Far from it. There seems to be a popular belief, at least in some newspapers, that the Wars of the Roses were some sort of non stop battle. It was far from it. One of the longest periods of peace in Medieval England can be found during these wars. There is on average less than one major battle per year during the Wars of the Roses. Indeed, if you add up the total number of weeks in which campaigning is known to have been undertaken on a grand scale, by the major nobles, it comes out at less than a years worth of campaigns over a 32 year period.

The Wars of the Roses was Lancashire v Yorkshire

This misunderstands where the names come from. This isn’t so much a newspaper error but more a general misconception. It’s one I saw people having at the start of the University of Oxford course on the Wars of the Roses. It is easy to think that the wars were geographically based around Lancaster and York. They are quite simply titles though. Land in both counties was held by supporters of both sides. The Neville family, for example, held a large amount of land in the north. Towton is a good example of this not being the case. The House of Lancaster had used York as a base from which they took to the battlefield at Towton. The Battle of Ferrybridge and Dingtindale both saw the Yorkshire based ‘Flower of Craven’ fighting on the side of the House of Lancaster. Huge swathes of land were controlled in this way. Even at the height of Richard, Duke of Gloucester’s power in the north there were supporters of the house of Lancaster in Yorkshire and Yorkists in Lancashire.

Richard Duke of Gloucester was guardian of Edward V

Not the case. Suggested by David Durose on the British Medieval History group. Many people believe that Richard was named as the guardian of Edward V. This would have seen him in charge of the young kings safety and would worsen claims made against him in relation to the fate of Edward and his brother. However, Richard wasn’t the guardian of Edward. Richard’s position following the death of Edward IV was Protector of the Realm. The appointed guardian of Edward was Earl Rivers.

Bosworth Field: Bibliography and Links

Richard III Society (America) Essays

University of Leicester: What did we know, when? (pdf file)

Richard III Society List of Primary Source locations

BBC History Extra. Article: Richard III was a great king who achieved more than Henry V or Elizabeth

BBC History Extra. Article: In case you missed it, Treachery at Bosworth, What really brought Richard down?

The Guardian. Article about Richard’s remains

Wars of the Roses Section

Causes of the Wars of the Roses – Course of the War of the Roses – Events of the War of the Roses

Battles in the Wars of the Roses

First Battle of St. Albans – Battle of Blore Heath – Battle of Ludford Bridge – Battle of Northampton – Battle of Wakefield – Battle of Mortimer’s Cross – Second Battle of St. Albans Battle of Ferrybridge – Battle of Towton – Battle of Hedgeley Moor – Battle of Hexham – Battle of Edgecote Moor – Battle of Losecote Field – Battle of Barnet – Battle of Tewkesbury – Battle of Bosworth – Battle of Stoke Field

Documents, Maps and Evidence

The Rous Rolls – Paston Letters – Edward IV Roll – Richard III’s letter to the people of York, 1483 – Historiography, Professor Carpenter on Edward IV

People and periods

British History – The Wars of the Roses – The Plantagenets – The Tudors – King Henry IV – King Henry V – King Henry VI – King Edward IV – King Edward V – King Richard III – King Henry VII – Margaret of Anjou – Richard, Duke of York – Richard Neville, Warwick the Kingmaker – Jack Cade – Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester

Schoolshistory – teaching resources for Key Stage 3, GCSE and A Level history