Vorkuta Gulag: Letters and Diaries of an inmate

Vorkuta Gulag and the surrounding area is one of the most isolated prison camps that has ever existed. Built in the arctic circle during Stalin’s rule, it housed prisoners of all kinds. Life was incredibly hard for those who were sent to Vorkuta. Documentary evidence of life in the prison set up is also quite rare. Prior to Stalin’s death, communication was severely limited. As outlined below, it was a few lines, in Russian, on an open postcard just a few times a year. This page hosts the letters and diaries of one Vorkuta inmate. Imprisoned for being an acquaintance, for 25 years.

The letters and diary extracts that appear on this page have been submitted to the site by the author Zenta Brice. The documents are from her families personal archive. I am incredibly grateful to Zenta for having the honour of being able to make these materials available.

The translation from Latvian and Russian into English has been undertaken by Zenta Brice herself to ensure that the translation is accurate. Editing of Zenta’s commentary has been undertaken by Kate from Portable Magic. Zenta’s novels, including a forthcoming one, are based on real-life events in the Baltic under Russian then Soviet rule. Her books can be found here. An interview about Zenta’s novel set in the period of the Soviet collapse can be found here: Author Interview: Zenta Brice on the fall of the USSR

The following introduction was written by Zenta Brice. Any of my own comments within the text will be highlighted as being an editorial addition.

Arrest and ‘Crime’

The author of the diary was dragged out of the classroom in 1949 for the crime he had no idea about. Only in the 1990’s did he finally see his criminal “case” and learn what he was accused for. The case was built around some distant uncle of one of his school friends. He never met the said farmer, who became one of the so-called “forest brothers” – anti-Soviet resistance after WWII, never even heard his name. But the state demanded numbers imprisoned, and KGB tried hard to provide. So he was added to the “case” as a friend of the nephew of the said farmer who was shot for daring to stand against forced Soviet agriculture policy.

Sentenced and transported to Vorkuta

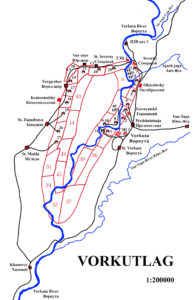

After about a year in the dreaded cells in a KGB cellar and endless interrogations, the eighteen year old author of the diary was tried by so-called Troika (fast speed, unqualified three-judge court) and got the maximum possible sentence under Article 58 of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic penal code: 25 years in prison and 5 years in restricted settlement after that, without rights to return home, ever. Then he was loaded in the train carriage and sent to one of the biggest and worst Soviet prison camps – Vorkuta, about 100 km beyond Arctic Circle in the North-Western part of the Soviet Union.

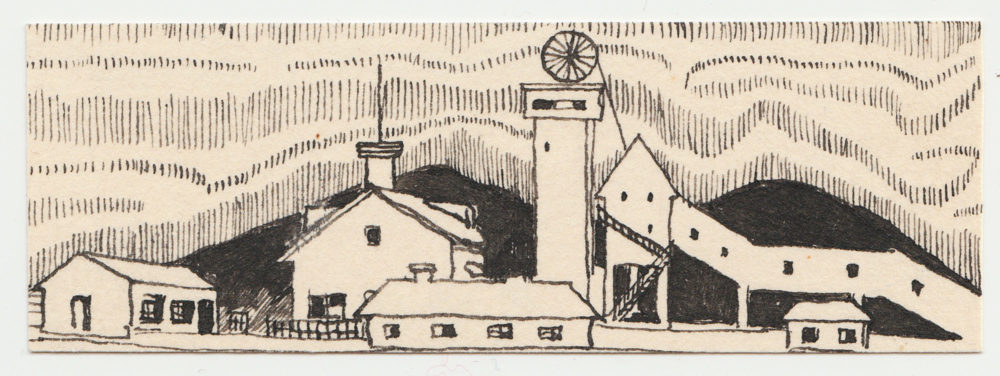

Prisoner Categories at Vorkuta Gulag

At the time, the Vorkuta mining area was inhabited by 3 different categories of people.

Soviet citizens – mostly office workers, prison guards and other contracted people with full citizenship, with no restrictions to their freedom and citizen rights.

About 100,000 deported people with limited rights and forced into labour, mainly in coal mines. (They still had relative freedom within restrictions)

About 100,000 prisoners, located in GULAG prison camps, with all civil rights removed, forced to work in mine shafts.

The GULAG is an acronym for the State Camp Administration. At the time there were about 30 camps with lice-infested barracks behind barbed wire stockades. The inmates included Soviet soldiers who had the misfortune to fall into enemy hands – first in the Soviet-Finnish War of 1939-40, then in World War II – and, according to Stalin’s doctrine, they were pronounced traitors. There were Ukrainians and Lithuanians rounded up as nationalists, as well as doctors and scholars suspected of harbouring unpatriotic ideas, and relatives of any of the above. Stalin trusted nobody.

Organisation of the Prisoners at Vorkuta

In prison camps, the true criminals were deliberately kept together with Prisoners Of War (POWs) and political prisoners, making lives of the latter even more miserable as they had no previous prison experience. Soviet policy in camps was to push each group against others to prevent unification and possible revolts. Criminals against political, Russians against Ukrainians, Russian POWs against German POWs, imprisoned Russian army officers against criminals, and so on.

Only the worst criminals were appointed as the brigade leaders. Political prisoners joined together to protect themselves from the brutality of these criminals.

There were two categories of criminals – ones ready to collaborate with Soviet forces – suki (bitches in Russian), and the ones who vigorously kept the code of honour of the underworld – blatnye. Blatnye treated collaborating suki as traitors.

Russian army officers joined with blatnye into eliminating collaborators, informers (stukachi, knockers in Russian) and worst, foremen.

Conditions in Vorkuta Gulag

By the time of the author’s arrival in 1949, the work conditions of prisoners had improved in comparison with the worst war years, prisoners worked along the “free” miners in two shifts, each 12 hours, with four work-free rest days each month, but the living conditions and allotted food were still miserable, and weaker prisoners still died from exhaustion and health complications.

Sometimes the prisoners were paid small wages which they were allowed to spend in the camp’s shop. One of the levers camps were able to use against prisoners was to put them in worst sectors where hardest work would still earn you penalty points for not completing the allocated amount, thus prisoners would not be able to earn wages. As a result, by 1952, in many cases, one group or another started to protest by refusing to work.

Tension in the Vorkuta Camp

The tensions in the camps grew during 1952, with the general opinion that if Stalin died, the camps must start a revolt. They referred to the expected death of Stalin as a “miracle”. Camp guards became more jumpy, ready to fire or put the dogs on the prisoners faster. At the same time, they realised that times can change and started to talk to the prisoners more often, especially to Russian army officers.

Finally, the death of Stalin was announced through the loudspeakers through all the camps in March 1953. Many prisoners cried while others went down on their knees as they listened to the news.

The celebrations continued after the first day. The work discipline crumbled, people started slacking, and in a few months the first prisoners were released, only criminals while there were no changes for political prisoners (58 others, nicknamed after Article 58 of the Penal code, which was widely applied to political prisoners – traitors).

Vorkuta Uprising

Editorial addition in italics.

Following the death of Stalin, there was a period in which authoritarian rule began to be relaxed. This raised levels of anticipation in camps such as Vorkuta. However, it soon became clear that whilst some prison sentences were being commuted, this was not going to be the case for everyone. The General Amnesty that was decreed in March of 1953 was only applicable to people with minor offences and relatively small prison terms. Vorkuta was home to prisoners with long sentences who had been convicted of crimes that remained to be seen as serious ones. Added to this was a growing tension in the Gulag between the different ethnic groups and the guards. In June 1953 a large number of Ukranian prisoners had been transferred to Vorkuta. Unlike the inmates from Russia, Poland and the Baltic States, they were not accustomed to the prison regime and were new inmates with freedom quite fresh in their minds. This led to tension which was soon transferred into other parts of the Gulag. At around the same time, the news trickled through to the Gulag that Lavrentiy Beria had been arrested in Moscow. Beria was widely regarded as being responsible for the imprisonment of many inmates in camps. His arrest led to talk of injustice. Added to frustration over the lack of Amnesty and the problems that had emerged within the different ethnic groups,it led to protest.

On 19th July 1953 one ‘department’ within the camp simply refused to go to work. As all of the sections of the camp complex could easily see each other, it was clear to other areas of the camp what was going on: quite simply, they could see that wheels were not turning and could infer that this was passive resistance from the lack of engineers being called to that site. The refusal to work spread quickly to another 5 sections or ‘departments’ as they were known in the camp system.

Soon, some 18000 prisoners were refusing to work. They demanded access to legal representation along with political demands. Senior officials flew in from Moscow as a result. It was one of the first open challenges to the regime following the death of Stalin. Decisions needed to be made carefully: act too harshly and the amnesties and other changes being introduced would be viewed with disdain by the public; fail to act and the peaceful revolt may escalate and occur elsewhere.

For a week the officials talked to inmates. Then, on 26th July a group of prisoners stormed the central compound. Here they released 77 inmates from the maximum security compound. This changed the authorities view of the situation. On 31st July a series of arrests were made of the ringleaders behind the strike. Prisoners responded by building barricades. In turn, the authorities opted to use force. On 1st August the order was given to open fire on those at the barricades.

The decision to open fire led to many deaths. The well known writer and dissident Solzhenitsyn states 66 died instantly. Another account says 42. Additionally there were more than 100 injured, many of whom would perish from their wounds. The Uprising was crushed as a result of these shootings.

Escaping from Vorkuta: An impossible dream

Escape from Vorkuta was impossible – not so much because of towers, searchlights and barbed wire fences, but because of climate and location. The only life around Vorkuta was in camps, the rest was inhabited tundra. Trying to walk 500 kilometres through bare tundra in winter, when temperatures drop down to -50 – 60C, would lead to certain death due to the cold. In summer it seemed a possibility, but walking the distance only on berries, available in the tundra, was a fantasy, plus the camps had planes which were used to search for escaped prisoners. As there is nowhere to hide in the tundra, no trees at all, finding the escaped prisoner was easy.

The only realistic route out of Vorkuta was in the open coal carriage, which travelled to Leningrad. Some of the prisoners built a small shelf in the carriage out of wooden planks to hide under and allowed themselves to be buried under the coal. When the first dead body under such a shelf was discovered at the end destination, guards started to check each loaded carriage with long iron pikes which they pushed through the coal right to the bottom of the carriage.

Psychological Impact of imprisonment: After release

When you read the diary, it’s full of books he reads, about art, cinema and sunbathing – it reads like a completely normal diary. Almost. In his diary, the author not even once mentions barbed wires and daily shifts down in mines, under the watchful eyes of armed guards. But the unwritten stayed with him for life – he wasn’t able to pat a dog, not even a cute puppy for the rest of his life as he was forced to watch as some of his friends were torn apart by dogs.

He doesn’t mention daily hunger and cold, but for the rest of his life, he was fighting with his failing health.

When he talks about sunbathing, please remember, he is not on his holidays in Spain. He is in the tundra, permafrost, spending most of his days under the surface, in the mines, so getting out on the good days and sitting in the sun is the part of survival as nights there are long.

So try to remember all of that when you read it. Read about what he doesn’t mention, that he pretends doesn’t exist in this little world which exists only in his diary.

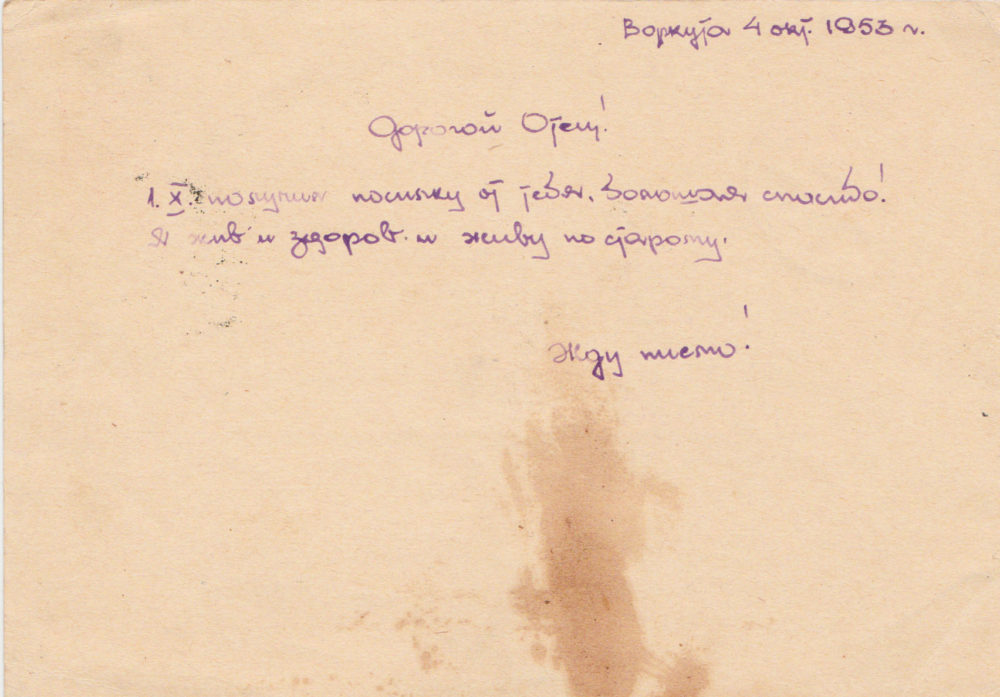

The author and his father were allowed to write to each other only a few letters per year, and they needed to be written in Russian, so censors had no problems reading them. This also remains unspoken in the diary. Until 1954, the author was allowed to write only a few, formal sentences on the open postcard.

Source Material: Diary and Letters, translated by Zenta Brice

DIARY

18th June 1955

Weather great, sunbathing. I’m reading Joffe all day, writing down many quotations.

Forced from home and all its pleasures Afric’s coast I left forlorn,

To increase a stranger’s treasures O’er the raging billows borne.

Still in thought as free as ever, What are England’s rights, I ask,

Me from my delights to sever, Me to torture, me to task ?

All sustained by patience, taught us Only by a broken heart… (W. Cowper)

19th June 1955

Today started to work on “Evening on Daugava River bank” painting. I’m thinking about painting it half expressionistically, but not sure if something good will come out of that.

Weather great, sunbathing. In the evening – cinema. “Brave people” [*Смелые люди, 1950] – complete rubbish.

At night the thunderstorm started. Great views at the horizon – on the greyish green background the wide tongues of the lightening danced endlessly. Hadn’t seen such a thunderstorm here, beyond Arctic Circle. In general, such thunderstorms are rare here.

20th June, 1955

Still reading Joffe. Made small figurine-ashtray. Tonight got a letter from Father, and also a package – three books. Weather really nice, sunbathing.

“The coward slave-we pass him by,

We dare be poor for a’ that!

For a’ that, an’ a’ that.

Our toils obscure an’ a’ that,

The rank is but the guinea’s stamp,

The Man’s the gowd for a’ that.” (Robert Burns)

21st June, 1955

Tried to work a bit on “Evening”. Didn’t go well. Primed a large canvas for my “bread job”[*with “bread job” he means copying popular paintings in his free time for private clients, mostly officers, in exchange for better food or even money while his main, mandatory job is still in coal mines]. Did read a bit of L.G. Weather good, sunbathed. Overcast at evening, started to rain.

“…you never will be hanged for the shooting of a swan.” (Polly Vaughn) Yeah, right.

22nd June, 1955

Reading Michelangelo by Huvera [*Guevara?]. B. came over, we talked about Michelangelo and antique sculpture. Also discussed impressionists. B. expressed opinion that in the near future, P.S. will definitely change his mind on impressionists as it is serious art which can’t be erased out of the world’s history of art.

Talking about sculpture, B. pointed to the indecisive balance point in antique paintings, while in sculptures of Michelangelo balance points are clear (David); except probably Bacchus where it’s not clear which leg is used as a main balance point.

Out of all Michelangelo’s sculptures I like Rome’s “Pieta” the most.

B. also drew my attention to Sistine Chapel, especially Apostle John, painted at the arch.

Had a bit to drink, struggling to write. Weather is turning colder.

“Perhaps You believed

I should find life hateful,

And flee to the wilderness

Because not all my blossom-dreams

Reached ripeness?”(Goethe, Prometheus)

23rd June,1955

Running all day for Midsummer* celebrations [*Latvians still celebrate pagan Summer solstice which is part of Latvian traditional culture], to make it proper. The celebration evening could turned out reasonably good, if only “my dearest friend” hadn’t tried hard to ruin it for me. Weather cold.

24th June, 1955

Slept all day, hangover. Weather cold.

25th June, 1955

Cinema in the morning. “Road to life” [*Путевка в жизнь, 1931]. Rather big piece of shit. Weather – bad. Had a good sleep at work today – almost 7 hours.

“It is invisible hands that torment and bend us the worst” (Nietzsche)

26th June, 1955

Played piano until noon [in club], was in that musical mood. Later did read a bit of dictionary. Then went to sleep, and slept all afternoon, until night. Weather still bad.

Amicus Plato, sed magis amica veritas.

27th June, 1955

Cinema in the morning. “Lomanosov” – weak. Did read “Michelangelo”, and later a bit of “G.” Had been thinking a lot about subjective and objective feeling of happiness and satisfaction. Is existence of objective feeling of happiness and satisfaction, also beauty, possible? Most likely not. Each subject can build feeling of happiness, satisfaction and beauty only individually, subjectively.

Doubting if these categories can exist outside the subject. Even more – classification of these feelings outside the subject seem impossible.

Weather bad, raining.

28th June, 1955

Reading “Michelangelo”. Got a letter from L. Interesting motto in it. “Good art exhibition is like Italian Opera – whatever the battles between tenors and baritones, the top note only castrate takes.”

Art is art and it depends on Nature only as an indicator, initial inspiration for a painting on art in general.

Who doesn’t understand this or doesn’t realize, has no talent or is simply a fool. As a typical example for such foolishness one can name Peredvizhniki [*Peredvizhniki Передви́жники, often called The Wanderers or The Itinerants in English, were a group of Russian realist artists who formed an artists’ cooperative in protest of academic restrictions; it evolved into the Society for Travelling Art Exhibitions in 1870] and especially Shishkin [*Ivan Ivanovich Shishkin, 1832 –1898) was a Russian landscape painter closely associated with the Peredvizhniki movement].

Weather bad, raining.

29th June, 1955

Went to see B. Talked about this and that. Find out about Schukin* [*shot for a skirmish with criminals, what he knew about him. Erio had been taken away [*relocated to another camp].

Reading “Isskustvo” [*Soviet art magazine] tonight.

30th June, 1955

Impressionism is page in the art which can’t be erased out of the history of art.

Wrote letters to L. and to Father.

Raining.

1st July, 1955.

Cinema in the morning. “The Government Inspector” [*Ревизор, 1952] – bearable, one can “escape”. Reading “Martin Eden”. Weather bad – raining.

2nd July, 1955

Holiday. Made four greetings cards. Reading a piece in Polish newspaper about Venice Biennale in 1945.

“A true work of art is the revelation of a new conception of life arising in the artist’s soul” (Tolstoy)

3rd July, 1955

Had my photo taken in the morning. Reading One Thousand and One Nights in English. Cinema – “A Comrade’s Honour” [* Честь товарища 1953] Later played piano a little. Weather overcast.

4th July, 1955

Still reading that piece in Polish newspaper “Dziś i Jutro” about Biennale in Venice, with big difficulties as my Polish isn’t that good. In cinema – “Dancing Pirate” [1936, USA]. Weather has improved.

5th July, 1955

Today is my 6th anniversary here. How many more years ahead for me and what they’ll bring?

Reading “Eden” in English, slowly, managed only two pages today.

Weather has improved finally – a bit warmer, with reduced amount of clouds.

7th July, 1955

Reading “Eden”. Was able to listen on radio Beethoven’s The Ruins of Athens, played by Ginzburg [*pianist Grigory Ginzburg, 1904-1961].

11th July, 1955

Reading “Martin Eden”. On cinema “Antoine and Antoinette” [*Antoine et Antoinette, 1947, France]. Cunningly made film, can watch with pleasure. Reading Kiplich.

Drew a portrait of Ceretely, pencil and touch. Sky overcast.

13th July, 1955

All morning had interesting conversations about Dostoevsky, Rilke, Nietzsche and Mayakovsky. Raskolnikov was more afraid of forgiveness, not so much of punishment. Cowardly heroism?

Weather nice. Learned English a bit. Head feels completely empty.

17th July, 1955

At work drew a few sketches in ink. Look at art prints, good drawings of Klimaschin for magazines. Chuikov’s Indian paintings also good.

18th July, 1955

Sunbathing, and reading “The Genius” by Dreiser in Russian, writing quotations. Wrote letter to Father, then went to sleep.

20th July, 1955

During the night draw “Švejk” [*The Good Soldier Švejk by Jaroslav Hašek]. Came out rather nice. Gave it to K. He promised to send me the book as soon as it will be released. Interesting, will he keep his promise?

21st July, 1955

Did some drawings of Don Quixote. Seems really suitable theme for me.

24th July, 1955

Weather nice, sunbathed. The events of 1953 repeat itself in the evening when the third shift refuses to start the work.

25th July, 1955

The first and the second shifts also refuse to go down the mine. The armed guards are removed from the towers. We will see how it develops.

The third shift goes to work, without guards for the first time.

It feels really weird. Six years and 21 days my every step was under the armed guards, and now suddenly you can walk alone.

26th July, 1955

In the morning, after the shift I still was able to go home alone. Absolutely wonderful.

At the same time it is impossible to read or think as air is filled with weird sensations, and I can’t say that it feels particularly good. More like a lump in the throat. Sky is overcast today and autumn is in the air.

2nd August, 1955

Nothing special is happening; everything is calm. Started to work on a self portrait, something like “Romantic youth”. I’m in a terrible mood, at the end of my tether. How long it will last, how long to cope?

The same thoughts go rounds in my head like an old, annoying melody, again and again. As soon as I try to think about anything, the old thoughts interrupt and take over, making it impossible to concentrate on anything, crushing in my head with the annoying rhythm. I’m in a miserable state, hope this will end soon, it’s unbearable.

Cold wind. Proper autumn.

3rd August, 1955

Miserable day for me as M. has left.

How horrible it feels, without him as we were tied together with so many invisible ties. Ten years… In theory, the ten best years of our life, full of thirst for knowledge and romanticism. Similar thoughts which lead to similar conclusions. Even though we had different opinions, we managed to find the common roots, and if that did not work we respected our disagreements.

The moments when we tried to solve our disagreements are stored in my memory as the best ones.

And now somebody disliked his face, and he was sent away, re-located. But I have a weird feeling that we parted for not so long as somehow our destinies are tied together. At least I can hope that it’s so.

But overall mood is dark, like bad times are ahead.

Today got a letter from L. He had been in Russia, and didn’t like it there. That’s how it should be.

Tonight heard a story, enough for a full novel. A worker in the shipyard. Stole. Run away on a ship. Ended up in French Legion in France. War. Forced work in Germany. Met a Latvian girl. After the war decided to return. Arrested, ended up in a camp here. Tried to escape. Death.

Grim story, but how many millions of similar ones?

Listened to radio tonight. Poetry, mostly Pushkin and some dekabrist, I already forgot his name. Poetry was good, really suitable for my mood. Music was suitable as well – Puccini, Manona Lesco.

4th August, 1955

Something wrong with my chest. Feels like lump in my throat is there forever. Maybe too much smoking? Or something more sinister there? I do not want to think about such a possibility. But it seems that I’ll need to see the doctor. Weather bad.

5th August, 1955

Started to paint “Winter view” for Misha. Worked till 2. Read a bit of Dreiser, and went to sleep. Weather without changes – bad.

6th August, 1955

In the evening they moved me to the “smaller” zone. Everything messy and disgustingly dirty there. Before relocation everyone was issued a pass, probably afraid that we could start an uprising. Weather cold.

7th August, 1955

Spent all day in zone, trying to find a place. Finally settled in 13th Barrack. Tried to read “The Genius” but the mood is bad, I can’t concentrate. Gutta cavat lapidem.

8th August. Got a letter from Father. Finished the winter painting. Started a new one, also winter. Sky overcast.

“There is something in the human spirit that will survive and prevail, there is a tiny and brilliant light burning in the heart of man that will not go out no matter how dark the world becomes.” (Leo Tolstoy)

24th August, 1955

Today they transferred me back to main zone.

“Year after year your solitude will grow stronger,

For your friends will quit and you’ll climb alone…” (Rainis, “Distant feeling in a blue evening” 1903)

3rd October, 1955

Ni foi ni loi.

“I’m rushing in the darkness, in the glacial desert,

A moon is shining somewhere? Somewhere, there’s a sun?” (A. Block)

“You still must leave me

My Earth standing

And my hut which You did not build,

And my hearth, home’s glowing

Fire which You begrudge me.” (Goethe, Prometheus)

11th March, 1956

Mozart’s Requiem. Wonderful sounds, telling the story of the past and future of the humanity.

“On a lone winter evening, when the frost has wrought a silence,…” (John Keats)

3rd July, 1956

Today I was called in by the commission. They looked at my case haphazardly, but I am under the impression that the outcome seems rather promising for me. We’ll see it in near future.

15th July, 1956

Got the rumours that my sentence had been lifted. The first to congratulate me was Sitchov, and also M. He assured me that’s for certain as he had seen my name on the list in the office. It means seven years, day by day. Rather heavy, but at least I’m alive.

Had a drink for the news, to oblivion.

17th July, 1956

Not going out for the work, but didn’t get the release – it had been “forgotten” in the office.

18th July, 1956

Got the release form, also finalized all the accounts with the camp. Now all I need to do is to wait for the permission to leave. Will they or will they not?

I’ll find it out tomorrow. Please, all the Saints, stand for me!

19th July, 1956

Spent all day in the queue, to register my release paper, but without a success. Rumours are circulating that the ones with family members not forcefully relocated, will get Passports issued.

20th July, 1956

Spent all day in the queue again, without a success.

21st July, 1956

Took my place in the queue at 3 am. Today I definitely must get my release papers `as my nerves can’t take this uncertainty anymore. Finally! They took 3 photos, and filled the long forms which means Passport! Thank God for that!

22th July, 1956

Beautiful day, sunbathing.

“Run-down and worn from daily rambles

I will forsake the bustling whims

To bring to mind the sores of troubles

And stir the former, bygone dreams…” (A.Block)

23rd July, 1956

Started to sort out my belongings, painted the holdall. In the evening went to get the Passport but it’s not ready. Maybe tomorrow?

24th July, 1956

Passport is still not ready, must try again tomorrow.

27th July, 1956

Finally got my Passport. Fully fledged citizen again. Wetted it with the champagne.

29th July, 1956

B arrived, we had a drink. I’m in a funny mood, there are rumours that they are conscripting us into the army.

30th July, 1956

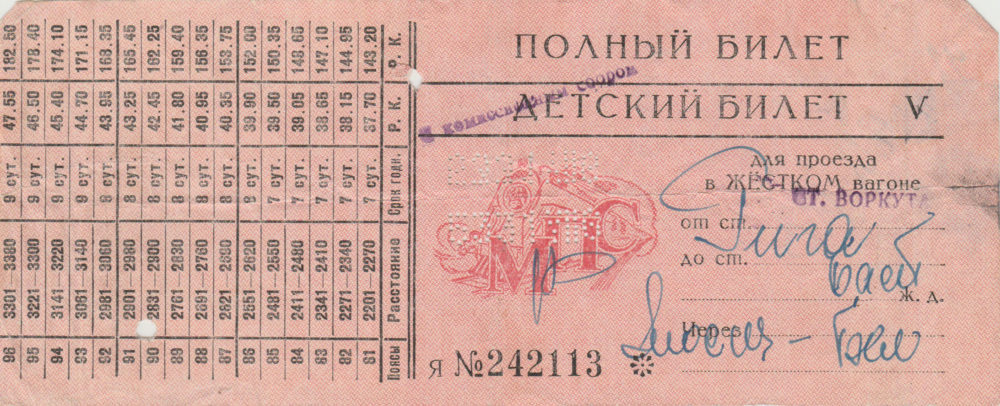

As it seems the day before last beyond the Arctic Circle for me as I was promised a train ticket tomorrow.

M arrived, and together we went to the mine, took photos. Said my farewells to M, need to pack everything – tomorrow night everything must be done as, I think, train leaves Vorkuta station at 22:15. I still must receive my money and purchase the ticket.

31st July, 1956

Got my ticket, through Moscow. Opened champagne.

A. went to station to get the “placard” but he returned with the card for the soft carriage! Isn’t it wonderful?

20:00. The train to Moscow leaves Vorkuta station. The last farewells to my comrades. And… GO!

My coupe is true luxury – soft furniture, mirrors, lights… The train starts to move…

Good bye, damned Vorkuta!

2nd August, 1956

The night. So unusual as this time of the year there is no night beyond the Arctic circle. The day went peacefully. Outside the first small trees – birches and willows. At the station went out to the market, bought tomatoes – they’re as expensive as in Vorkuta. Sat with S. and talked about this and that.

Washed myself and went to bed. I can sleep like a king – The seat has springs, mattress on top, proper feather pillow, white sheets… Luxury.

The next day stepped out in Velsk station and bought wild strawberries. The real wild strawberries, not the cloudberries [*Rubus chamaemorus]. Seven long years I hadn’t tasted them.

3rd August, 1956

In the morning we’re crossing Volga river. At 13:00 we arrive in Moscow. Left my bag at Riga station and off to Tretyakov Gallery. Spent the half day there, then took a taxi and did a round around Moscow. Walked on foot as well, about 8 km or so. At 22:10 train leaves to Riga. I’m going home!

4th August, 1956

When I woke up, train was already in Novosokolniki.

1st September 1956

Returned to school. Will see how it goes.

7th October, 1956

I’m in a terrible mood. Damned life, world and especially people. False money they are, indeed.

28th October, 1956

I’m in hospital*. They’re doing different tests. Called O, to wish her all the best on her birthday. Hospital is horrible, so boring, I want out.

[*psychiatric hospital. He suffered from depression and anxiety all his life]

28th July, 1957

Today I finally graduated from the Art college. Finally…

23rd August, 1957

Got the exam results. I’m in. I will continue as a student of the Academy of Art. So it continues…

LETTERS

Editorial note: the comments in brackets are Zenta Brice’s notes.

Son in Vorkuta, to Father back at home. All these letters had been written on a blank postcards, in Russian with very restricted content permitted only (hard censorship).

5th June, 1950* [written in Russian]

Hello, Father! All four of your parcels received in May as well as the money transfer. Thank you. Your son

[*This is the first news his father received for over the year, since the arrest in 1949. Father was able to find info that his son is alive, and able to send a permitted amount of parcels (also strongly regulated with regard to what can be sent).]

31st March, 1951 [written in Russian]

Hello, dear Father! Your parcel received in full*, big thank you. Please can you send me a shirt, a sheet and a rubber boots in the next parcel?

Money transfers now can be sent directly to my personal account through the bank.

With well wishes from all my heart

Your son

[*nothing had been confiscated or simply stolen]

2nd August , 1951 [written in Russian]

Hello, dear Father! Your parcel received, thank you. Please can you send me 150 rubles? Your son

3rd February, 1952 [written in Russian]

Hello, dear Father! Your parcel received, thank you. I’m all right and health is good.

Your son

11th July, 1952 [written in Russian]

Hello, dear Father! Your parcel received in full on 10th July, thank you very much. Your son

8th October, 1952 [written in Russian]

Dear Father! Your parcel received, thank you so very much. Do not send money anymore.

Your son

23rd August, 1953 [written in Russian]

Dear Father! Your parcel received in full, thank you very much. I’m all right and health is good.

Your son

4 October, 1953 [written in Russian]

Dear Father! Your parcel received on 1st October, thank you so very much. I’m all right, health is good, Living as before, no changes*.

Your son

[*Stalin died on March 5, 1953, and everybody expected changes to start happening]

Father back at home, to Son in Vorkuta

6th October, 1952 [written in Russian]

Greetings, dear son, from me and others, first of all from L., K. and young L. Old L., his father, over a year since died.

My life is not that well, working in Olaine cooperative bakery. Can’t work in Riga now as my Russian is not sufficient, you do understand*, so I’m back in the bakery as years ago where I started as apprentice. My leg has healed well, I’m not limping anymore and don’t feel it much now, so everything is all right again. Only my heart is messing with me now but I’ll try to heal it as much as possible. Doctor gave me drops.

I had sent you a winter hat, new, with sheep skin lining, and mittens.

Keep warm and stay safe.

Your Father

[*as he’s a father of a traitor, he is not permitted to work in the city anymore, so must work outside, in small towns. His Russian was very good as he was married to a Russian]

3rd March, 1953 [written in Russian]

Sending you my heartfelt greetings.

I’m living the old way. Thank God, I’m holding together rather well, and have enough strength to carry on working. In a few days I’ll send you a parcel – I got you glasses, No3, and the others, you know, -3.

I wish you all the best, especially good health.

Your Father.

9th September, 1953 [written in Russian]

Dear son, the parcel with my heartfelt well wishes had been sent.

I’m living the same old life, working in Kemeri* [Kemeri was a good convalescent home] now, and feeling well. Sent you the second parcel, after the break, but can’t send you the glasses as I can’t get any – not possible right now.

The summer passed here as usual, now autumn is here – raining every day, weather is not great. Now about the ones who are gone. Old L. died, and also your Aunt I told you about. Two months ago also old Lauce died, from a heart attack. Also Maria – remember, she visited often when you were still at home. She died about two years ago, but I found out only recently* [died in Siberian exile so death news come slowly, indirectly].

I got your letter, thank you! I will love you until my old eyes will close for the last time, dear son, XXXXXXX [*tree lines blackened by censorship] and wait for the parcel to arrive. Write to me as soon as you need something.

Your Father

17th January, 1954 [written in Russian]

Got your letter today. Thank you so much!

I’m living the same, still working at the same place. How the future will unfold I have no idea but I hope for better now, thank God. My health is all right, like an old ox, living from day to day. Passed one day – good enough for me. Greetings from K., E. and all others.

Hope to see you again, son! Hugs!

Your father

6th September, 1954 [written in Russian]

Thank you so much for your letter which I received on 15th August. I even had a drink to celebrate the good news* [*regulations had been loosened up in Vorkuta after the uprising and Stalin’s death].

During the summer I was really busy, six weeks worked in a row, without a break, but now it’s a bit better and I’ll have a day off more often. I started on a new job, restaurant Astoria, where your friend Cirulis also works, back in the cake department. But he works mainly during the day while I’m on the night shift with another four people. The pay is better than in Metro [restaurant, so he is permitted again to work in the city].

Sent you a parcel, with all your paints and brushes*, as you asked [*parcel regulations had been loosened up].

I’m living in one room now, the 2 other rooms I rented out. Your friend G.C. is married now, he married a nice cashier from Opera.

I’m all right, if you take into account my age – I’ll be 65 on 9th October, but I can work rather well still. It’s only lonely now, as I’m alone. But you do not worry, I have all I need.

If you need dentist, go for it, I will send money if you need it. Save your teeth!

You wrote about these good news – If you can, tell me more as I’m very interested, full of hope now.

Greetings to you from G.C. and Leon. He is playing in the restaurant Moskva now.

If you’ll be writing, send a few separate sentences for C.

I do not know if I’ll ever meet you again, dear son, so just know that I love you and think about you every day.

Your old Father

10th December 1954 [written in Russian]

Hello, dear Son from all our friends, and especially from your Aunt and Uncle! I wish you a Happy New Year!

I am sending you a parcel. In it will be your jacket. Listen now, I want to send you the fabric for a suit. I bought one, 3 meters for 400 rubles, and another one 3 meters, for 300 rubles. I also have fabric for lining, but would you be able to find someone to make it for you? I’ll be sending money as well, so you can pay. So write me in detail if there is a tailor or now. I wanted to buy you a ready one, but I do not know your size now. Also, there were not good ones, not double breasted. Do not worry about costs, I’m living alone, like a fence post, so I do not need much. I’m earning rather well now, not spending much on food and wood.

Sending you hugs and kisses, and wish you all the best.

Your Father

5th April, 1955 [*written in Latvian for the first time – censorship regulations are loosened and they can write to each other in their own language for the first time]

Dear son, big thank you for your letter and photos. You look well but your friend M. seems rather ill, but I might be mistaken. Let’s hope I’m mistaken.

I am not writing you much as I’m working 12-13 hour shifts now, and when I return home I often have not enough strength left to light the stove, I just crash into bed to sleep.

It’s not that I’m ill, but at 66 now I start to feel my age. But it’s good that I can still keep working. Last month I was ill, got cold. Doctor checked me all over – high blood pressure, enlarged heart and my old chronic bronchitis playing up, but that’s nothing – all old people have some itch here and there.

I know, son, that you think I’m struggling but I’m all right still, so do not worry. I found you a decent suit and also shoes which I will send soon.

You didn’t write me the last time if I can send or not now. I sent you the paints and brushes, and a bag last time, and you didn’t write to me if you did receive them or not. So you send me a response to send them or not now. They are waiting for you.

Sorry I’m not writing much, but I can’t write easy chit-chat son, you know, and letters take such a long time. Don’t spend your money on more photos as I had seen you now, you better use that money on food. I’ll try to get a photo as well so I can send you one.

You reply as soon as you can about the suit, to send it or not, and maybe you need something else – do not hesitate to ask, I can afford it. Greetings to your friend M. I wish you both great Easter.

Loving hugs and kisses to you, my dear son, from

Your old Father

22nd April, 1955 [written in Latvian]

Thank you for your letter which I received on 17th, exactly on Orthodox celebrations [*Easter]. I’m still the same, only on 18th I took a week off, while they renovate the kitchens. Worked hard all through the holidays, only on second morning of Orthodox [Easter] went home, lit the stove, went to sauna and then took a good nap. Later I returned to work and with colleagues we went to Luna [restaurant] to celebrate Easter. We had a dinner, and a bit of Vodka. Your friend C. was with us as well. After the restaurant we went to one of the colleagues where we partied until midnight. The next day I slept all day long as my head was seriously heavy. To be honest, I can’t drink at all as alcohol sends my blood pressure through the roof, but I drink rarely. There is nothing much one can do when you meet with others.

Here everything is the same only prices going up. Because of Easter, price of butter reached 50 rubles per kilo. Eggs were 17 rubles for 10. I didn’t bought any – I eat in canteen, and also at work.

I had a conversation with your friend. I so want to go to visit you, to see you, exchange a few sentences, but it seems impossible. I should have enough money but for such a trip I need about a month off work, but I’ll get only two weeks in August as I took that one week when they were renovating the kitchens. Oh well, destiny of ours. Did you manage to get the new front teeth?

I nearly bought a nice piano for you, but was a bit short. They wanted 11 thousand for it, but I needed to pay for that coat I ordered at tailor.

Warmest kisses and hugs to you, son! I so hope you will be able to return home soon as many already had been released and are returning home.

Your Father

8th October, 1955 [written in Latvian]

Thank you, my dear son, for your letter. I did read it and it made me really happy. If it’s as you wrote, it would be big positive change for you and all the people there.

Don’t you worry about the coat, you’ll get it. It’s not that I have no money, I just need to find where I can buy one, but I’ll find one. Your hat has survived well these years, so no worries. I’ll buy also a flatcap for you.

You write that potatoes in Vorkuta are 4 roubles per kilo, but potatoes here, in Riga, three weeks ago also were expensive – 3 roubles per kilo. Now they are 1 rouble and 50 kopeks. You wrote that two apples cost 5 roubles, which is around half a kilo. Best apples here also cost 10-12 roubles per kilo. The best tomatoes here cost 5-6 roubles per kilo – they all grow here but still so expensive.

Everything else also is rather expensive on the market now – lamp is 18-20 roubles, beef – 16-18, butter – 40-45 roubles per kilo. State shops are cheaper.

Weather here is still warm and very nice. A cruise ship from Denmark was in Riga, many Latvians and Russians was on it, as tourists. They were met with delegation, with flowers, and they were allowed to choose where to stay – in the hotel or with relatives if they have such.

I’m well and perky, thank God for that, still working in the same place.

I wish you all the best, my son, be obedient and submissive, and then all will be good at the end. My only suggestion – try not to drink, alcohol is the damnation of the humankind.

Kisses and loving hugs to you, my son.

Your old Father

8th November 1955 [written in Latvian]

Many greetings to you, Son! Thank you for your letter, I did received it but was too busy to reply right away as I was working long shifts before that holiday [*7th November, anniversary of Revolution]. I was working 12 hour shifts, days and nights, but there is no choice if you need to earn some. I must admit that I earned quite well. I bought you a new coat, rather neat, you will be not ashamed to wear it, I think.

Me myself living and working as before. I’m well, only bones are getting stiff, but still able to work in full, so do not worry.

I will send you the coat as soon as possible. I was hoping to send it right away, but I had day shifts, all day long. But after the holidays I will be working night shifts, so I’ll be able to go to Post Office.

Best wishes and hugs to you Son, hope you will be home soon.

Your Father