How did Edward IV take the throne of England in 1461?

How did Edward IV take the throne of England?

1461: Bad news travels fast.

On December 30th 1460 disaster struck the Yorkist cause. At the Battle of Wakefield Richard duke of York, Edmund Earl of Rutland and the Earl of Salisbury were all killed in or shortly after the battle. The Yorkist army that had intended to enforce the Act of Accord was destroyed. This news travelled quickly throughout the realm. Bad news travels fast. It reached London within days. The Earl of March, now the prominent member of the House of York, received news of the deaths of his father and brother whilst at Ludlow, South Wales. In the north, Queen Margaret was jubilant. Richard’s head was displayed on a spike as that of a traitor. Her army was ready for the next phase of what they assumed would be a rapid and decisive victory for the House of Lancaster.

The Yorkist options

Students need to consider the situation for the two opposing sides at this point. The Yorkists had lost key leaders but, crucially, not all of them. There remained the Earl of March, now heir apparent to the throne under the terms of the Act of Accord, along with the Earl of Warwick. Both of these men held great power. Edward through his father’s title and his claims to them, Warwick as the most powerful magnate in the land. Furthermore, the Yorkists had two important advantages over Margaret of Anjou. First, they had Henry VI in their custody. Second, they held London, the seat of government and the most important of English commercial cities. A weakness, however, was that Edward was in Wales, far from the places where actions needed to happen.

Questions for students about the Yorkist situation at this time

- What are the immediate priorities of the Yorkists following the Battle of Wakefield?

- What is the biggest threat to Edward and Warwick?

- What legal grounds can the Yorkists refer to gain additional support from people?

- Are the Yorkists in a position of strength or weakness at this time?

Edward intended to make his way to London. Warwick too was in London where he made preparations for the defence of the city and busied himself making preparations for conflict. Henry VI remained locked in the Tower of London.

Margaret of Anjou’s reaction to the Battle of Wakefield

The Battle of Wakefield offered Margaret of Anjou great hope. She has opposed the Act of Accord as it had stripped her son of his right to inherit. Now, the man who had forced that change along with his eldest son was dead. The House of York was now headed by a young man. In politics and on the battlefield experience counts for a great deal. Margaret has the backing of many nobles against the Earl of Warwick and the young Edward. She also has a large Scottish force and many mercenaries at her disposal. Her problem is that her husband, King Henry VI is in London, in the custody of the Earl of Warwick.

Questions for students about the situation that Margaret of Anjou was in at this time

- What are Margaret’s main priorities at this time?

- Does Margaret need to do anything?

- Could Margaret establish an alternative court, centred around her son, at York? If so, what would the implications be? If not, why not?

- Does Margaret have enough support to forcibly resolve the issues in her favour?

Playing to the crowd: who will support each side in the inevitable conflict?

With large scale conflict looking quite likely both sides needed to address the matter of recruitment. Both had large mobilised forces, though neither could be certain that this would be large enough though. Ask students to consider the following groups and decide which side they think each group would be most likely to support.

- The upper nobility. Barons and Earls. Consider who gave them their titles, who can take away those titles and the beliefs of the day about anointed monarchs. Also, consider the attitude of the Council in the years leading to this point. Who had they sided with then? Is there anything to suggest that they would alter allegiances now?

- The gentry. The lower level of nobility and reasonably wealthy commoners. Consider the attitude of these people towards the two rival factions as tension grew. Who had they backed in previous clashes? What had the gentry done during uprisings such as the Cade Rebellion?

- The commons. Members of Parliament, Merchants and suchlike. These people have influence. They own property, have financial might, govern, conduct England’s trade with the outside world. Had they been satisfied in the years leading to this situation? If not, who did they blame?

- The ports and the navy. These are critical in terms of getting overseas assistance. They also enable the movement of ordnance around the coast quite quickly, giving a lot of firepower on the battlefield that the other side may not have. They also impact on imports and exports, so have a huge bearing on the economic wellbeing of the nation. Who controls the ports and navy?

- Can students think of any other groups that ought to be considered?

Of course, within each of those categories, there will be some people who chose either side, plus others who decide against any involvement at all. Asking students to consider it in general terms gives them an understanding of the context in which events are being played out. Margaret of Anjou may have won a major victory at Wakefield but she and her council were widely disliked. Calais and other major ports were loyal to Warwick, due to his position there: he was in control of Calais as these events occurred. You could refer back to Cade’s rebellion, the people had taken a stance that virtually mirrors the claims of loyal opposition that had been made by Richard. Groups that are missing from the bullet points include the church, who can legitimise a claim and fund a campaign; the French, who can contribute men or funds; Burgundy, for the same reasons; Ireland, from where Richard had made his landing.

St. Alban’s: Yorkist failure?

Margaret’s primary objectives were to regain control of her husband and London. These two things would effectively put her in control and enable her to overturn the Act of Accord. Her army marched south, in a broad sweep following the path of the Great North Road. The march south is noted for the looting that occurred en route. As the army marched south it lost some of the Scots and mercenaries. In part, this was due to the relative lack of funds available to the Lancastrians at this time. Warwick decided to meet the challenges head-on. Edward needed to be in London, plans needed to be made and the future of a Yorkist (Warwick dominated) government needed to be organised. To do that, he has to stop Margaret and avenge his father’s death.

Warwick chose St. Alban’s as the place where he would challenge the Lancastrian army. The town was well known to him, was easy to defend and was close enough to London for a force to be deployed reasonably easily. See our page on the 2nd Battle of St. Alban’s for a description of the battle.

At the second battle of St. Alban’s Warwick was forced to retreat as Sir Anthony Trollope led his men on an unexpected and highly successful attack. This resulted in the Yorkists withdrawing to London.

Importantly, the Yorkists left King Henry VI on the battlefield with two knights to ensure his safety. Margaret had Henry in her care again. On the battlefield, she had her son knighted, aged 7. The newly knighted Edward then presided over a quick trial of the two men who had guarded the king. Both were executed as a result: believed to be against King Henry’s wishes but I have no concrete proof either way on that.

Questions about the 2nd Battle of St. Alban’s

- What is the major gain for the Lancastrians from this battle?

- How will news of the guards being executed be received throughout the land?

- Has the Yorkist army really been defeated?

- What are the objectives now for both Margaret and Warwick?

Note that Edward was still masking his way to join with Warwick at this point.

At the gates of London

News of the actions of Margaret’s armies behaviour on the March south had reached London before her army approached. So too had the Earl of Warwick returned and bolstered the cities defences. Edward had arrived and been proclaimed King by the Yorkists.

Questions about Margaret’s arrival at London

- Are the ordinary citizens of London sympathetic towards Margaret?

- Who is in control of the Tower of London and it’s armoury and arsenal?

- What is the significance of Edwards arrival in London?

- London at the time was a walled city. Has Margaret got a realistic chance of capturing the city?

- With Henry safely in Lancastrian care, is there any need for Margaret to take any chances?

- Where is Margaret most likely to have widespread support?

Margaret of Anjou and her commanders decided against an assault on London. They were ill-equipped for a prolonged siege and had no real need to take the city at this time. London was firmly behind the newly declared King Edward IV and the Yorkist forces were now heavily concentrated around the capital. Students may remember that for long periods the Queen had based her court in the Midlands. The Parliament of Devils had been held in Coventry. Now she held a strategic advantage in the north of England. Much of the nobility were supportive of the claim of Prince Edward and loyal to the anointed King Henry VI. So, her army returned to York from where they could control any military proceedings with many factors on their side.

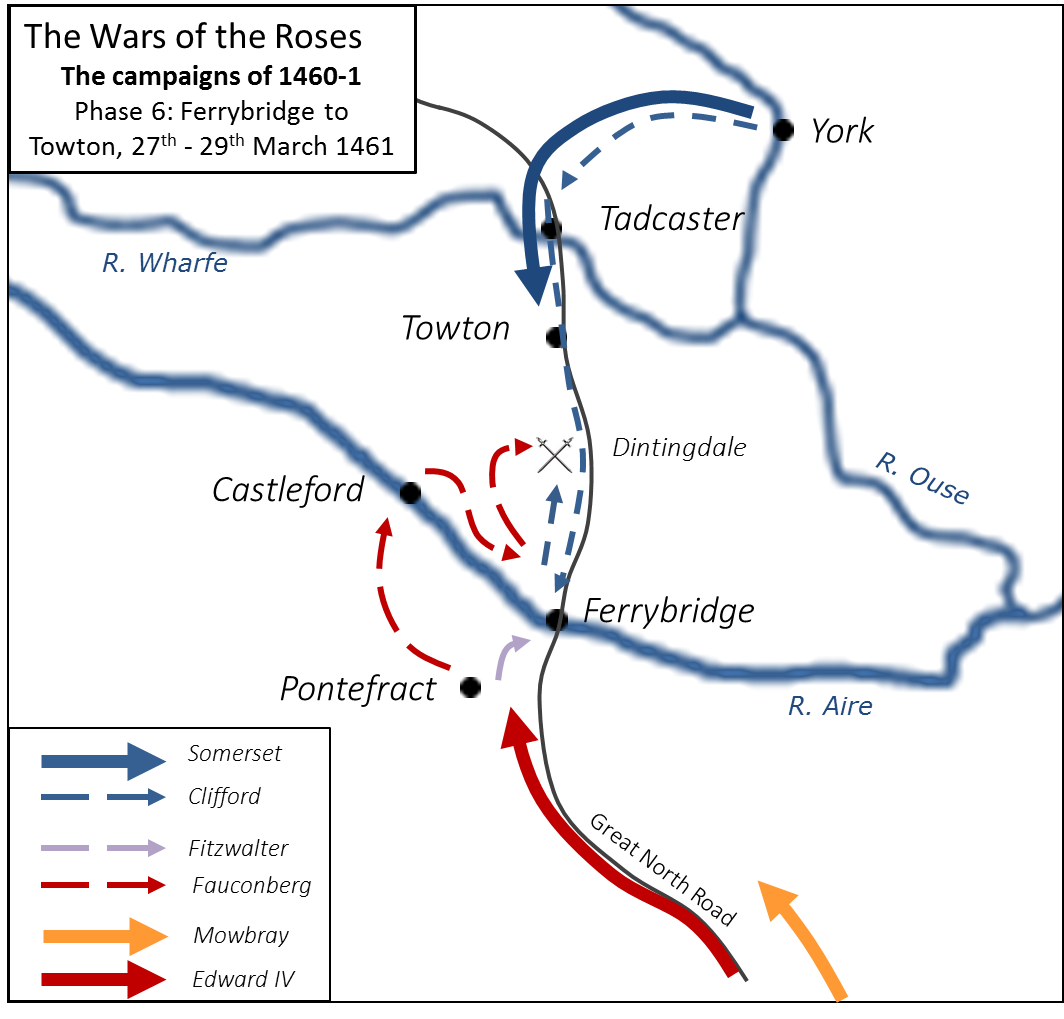

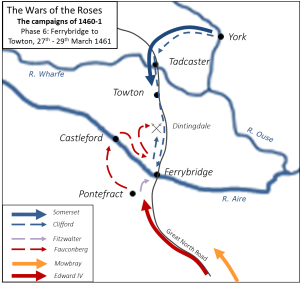

Movement of leading protagonists January to March 1461

Preparations

Warwick was reunited with Edward shortly after St. Alban’s. On the way to London, it was decided that Edward should be declared king. He was far more popular that Henry VI, less divisive than his father had been and, for the citizens of London, offered hope against the marauding Lancastrians. Edward was now known as King Edward IV and immediately enjoyed support from many quarters. However, he still had Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou to deal with and a large army to defeat if he was to retain the newly claimed crown.

Preparations began for a campaign in the north. First, Edward sent messages to all sheriff in England imploring them to accept him and as King and to offer him their support. Second, he offered pardons to any Lancastrian who submitted in the next ten days, a move designed to win over common men and lower gentry. Third, he issued commissions of array, the formal process of a call to arms. Warwick went to the midlands to recruit. John Fogge and Robert Horne were sent to Kent to recruit there. The Duke of Norfolk promised to recruit from his estates in East Anglia and to follow Edward north as soon as he was well enough. Support was also forthcoming from overseas. The Duke of Burgundy arrived with a force of hand gunners. Faucenburg arrived with a force from the garrison in Calais.

In the north, the Lancastrian lords looked to bolster their army. Many men had already joined, more were sought out. They had a huge number of estates to draw upon and the safety of York’s impressive defences from which to plan their operations. They knew that the Yorkists would need to follow the Great North Road. This allowed them to identify the crossing points of rivers that Edward would need to cross: enabling relatively easy assaults on the Yorkist force with minimal losses to themselves. They could also choose the battlefield as the routes from these crossing points to York are limited.

Both sides had suffered losses of leaders. The Yorkists had lost Richard, Duke of York, Edmund Earl of Rutland and the Earl of Salisbury. The Lancastrians had lost Buckingham, Shrewsbury, Egremont and Beaumont.

Questions about the preparations for war

- Which army is likely to have the upper hand in a northern campaign?

- Which army can claim the legal right to rule?

- Which side will the majority of the nobility side with? Why?

- Which side will the majority of the gentry and commons side with? Why?

- Which side controls the sites of battles and strategic locations along the campaign trail? How big an advantage is this?

- What logistical problems will the two armies have to overcome during a campaign? Which side is better equipped to deal with these in the north?

Ferrybridge and Dintingdale

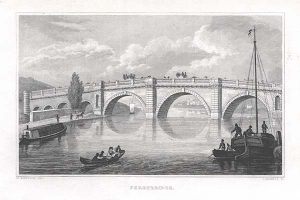

This is not a medieval image but it is of Ferrybridge. It illustrates the scale of the problem faced by any advancing army heading north. The river is wide and deep enough for merchant shipping. Put simply, you need to control the bridge to get north. The alternatives would be a match from Pontefract, now in Yorkist hands as it had been abandoned by the Lancastrians, to Leeds where there was a similar bridge or to ford the river at nearby Castleford. The problem with fording the river is that this is slow and the baggage train is not suited to the process, it also poses a huge problem for the transport of gunpowder. Leeds simply presents a long march followed by exactly the same problem for attackers but with the added disadvantage of having to assault a bridge in an urban setting.

Questions: the importance of Ferrybridge

- Who controls the bridge?

- Why is the bridge important?

- How easy is it to defend a bridge? What can the defenders do to make a crossing or making it harder?

- Why can’t the Yorkists just take a different route?

- Which side has the advantage?

- How can the advantage be overcome?

The advantage at Ferrybridge lay very much with the defending Lancastrian force. They can defend the bridge with a relatively small number of men as the advancing Yorkists have to funnel themselves onto the bridge itself. They can also make efforts to destroy the bridge. In the event, the bridge was assaulted several times. The Earl of Warwick was injured in these attacks. To overcome the huge advantage that the Lancastrians had at Ferrybridge the Yorkists sent a flanking force over the river at the ford at Castleford. As a result of this, the Lancastrians defending the bridge faced an attack to the side as well as on the bridge. Consequently, on the second assault on the bridge, it fell into Yorkist hands and they were able to secure it for the main armies crossing.

This image shows how the Yorkists used a flanking manoeuvre to take Ferrybridge.

The Lancastrians had additional forces in advanced positions. This is to harass the advance of the Yorkists and to enable the main army to have ample warning of an imminent attack. At Dintingdale they had a force led by Lord Clifford and his horsemen, known as ‘the flower of Craven’ along with John Neville of the Westmoreland branch of the Neville family: note here that the Neville family themselves are on opposing sides in the campaign.

Dintingdale saw a resounding Yorkist victory over the small Lancastrian force with both Clifford and John Neville perishing in the fight. It opened up the route for the set-piece battle between the two armies.

Towton: the battle for the crown

The course of the battle is not particularly relevant to the political ramifications upon which A-Level courses focus. However, should you wish to read about the way that the battle was fought we have a detailed page about it here: The Battle of Towton.

Towton: the basics

Size of armies: contemporary accounts are notoriously unreliable in the figures that they provide for medieval battles. One source suggests up to 100,000 men participated in the battle. This seems rather implausible as that would be 4% of the entire English population of the day. It is true that is was a huge battle though and the figures are staggering. Modern historians still debate the numbers involved but as a general guide they tend to suggest figures along the lines of:

Lancastrian Army 30-35000

Yorkist Army 20-25000 (plus 5000 that the Duke of Norfolk had which were not on the battlefield)

Site of the Battle: this had been chosen by the Lancastrian commanders. The fields between Towton and Saxton are undulating with a gradual rise. Choosing this site meant that the Lancastrians held the higher ground and had the advantage of the rolling landscape. To one side of the site was Castle Hill Wood, with a slope and Cock Beck at its foot. This meant that this side could not be used for outflanking manoeuvres. On the other side was boggy ground that was unsuited to any kind of movement of armed men or horses. This left an area roughly 400 metres wide in which the fighting would take place.

Tactics: usually a medieval army would line up in 3 battles. A battle being a significant part of the army. With a reserve to the rear and baggage behind that. The narrow field of battle at Towton changed the formation. To the fore came the vanguard followed by two further battles and then the reserve. In the case of the Yorkists, there was also the Duke of Norfolk making his way to the battlefield. Behind the Lancastrian line was a route back to York that included another dependable river crossing over the Ouse. Both sides opted to line up their archers ahead of their vanguards, which would see an exchange of arrows being loosed in order to try and inflict much damage beforehand to hand combat.

Conditions: here we see one of the critical factors in the events of the day. Towton opened in Blizzard conditions. The wind was coming from behind the Yorkists into the faces of the Lancastrians. The blizzard included hail and snow, making conditions very cold, wet, slippery and quite unsuitable for the use of gunpowder at the opening of the battle.

Questions about the battlefield and conditions at Towton

- Which army held the advantage at the beginning of the battle? Why do you think about this?

- How significant is the choice of location? How does it help the defenders and hinder the attackers?

- What impact might the weather have on the fighting?

- Why have the Lancastrians chosen a site where flanking can not take place?

- Based on the size of armies, site of battle and conditions on the day, who would you expect to be victorious in this battle? Why do you think this?

The weather did play a significant role in the opening exchanges of the battle. You can read about it in Battle in a Blizzard. In brief terms, it allowed archers under Faucenburg’s command to advance, lose arrows with the wind helping them fly further, then retreat. This was repeated over and over again. It meant that Yorkist arrows were going into the massed ranks of the Lancastrians but the Lancastrians, unable to see what the Yorkists were doing, we’re losing volleys of arrows that we’re falling short of the enemy.

This unexpected benefit of the weather does not give the Yorkists a massive advantage though. If anything it evens things out and negates the benefits that the Lancastrians had from holding the upper ground. It still meant that the two forces would have to meet head-on in hand to hand combat. And these are two massive armies, the fighting lasted for a long time with neither side having a huge advantage.

What changed things from being a hard-fought but bodily equal contest into a victory was the arrival of the Duke of Norfolk. Though his men had been marching, this is incredibly ‘fresh’ compared to forces who have been fighting for a long time. The arrival of such a large force swayed things quickly in favour of the Yorkists. Lancastrian lines broke and many began to try to flee the battlefield. They did so by trying to get into the woods and across Cock Beck: there couldn’t simply retreat as there were men behind them. As they went down the hill many slipped and fell, others struggled to get around them. Yorkist archers slew many of them, followed by a rout in which thousands of Lancastrians were killed.

The Battle of Towton was won, as with numbers of participants it is impossible to say for sure how many died but the most commonly used figure is 28,000 dead: 1% of England’s population.

Questions about the Battle of Towton

- How did the Yorkists manage to win the Battle of Towton? You can refer to our page on the battle and source pack (coming soon)

- Which political figures were not on the battlefield?

Responses to Towton: Where next for the political opponents?

- Edward IV has won a major victory at Towton. Most of the Lancastrian nobility is dead. How secure is his position now?

- Margaret of Anjou, Prince Edward and King Henry VI were in York rather than at the battlefield. What are their options now?

- What should Edward and Warwick do with captured Lancastrian nobles?

- What will be the implications of such a large battle and decisive victory politically, economically and socially?

Links

Battle in a Blizzard: Palm Sunday 1461

Source Material on the Wars of the Roses (General)

Support for Edward, Earl of March in 1460-61

Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick