One of the main issues facing A-Level students as they begin a study of the Wars of the Roses is that of context. They may be familiar with some of the main characters, know a little about key events, have an awareness of the Hundred Years War. So too, they may have preconceived ideas about the personalities of the chief protagonists. What they are unlikely to have though, is an understanding of how this fits into society at that time.

With limited awareness of society at the time, students will be unable to grasp the full nature of the socio-political situation in England in the years building up to the outbreak of the Wars of the Roses.

Medieval Mindset

Ask students what they think constituted a good Medieval monarch. Brainstorm that issue and the odds are that they will come up with something like:

- Strong

- Just

- Fair

- Victorious in Battle

- Legitimate

- And other such things about effective leadership…

If they have done any preparatory reading, you could ask them to describe Henry VI. In that case, it is likely that they would be less than complimentary. Weak, Feeble, Cowardly, Easily Led, Pious etc would most often come up. Nothing wrong with the piety, the rest are as far removed from effective monarchy as is imaginable though.

The issue here is that they are most probably applying today’s definitions of these terms to rather limited knowledge: and doing that at the outset of the course can have grave consequences when tackling issues later in their studies.

So, how can you introduce students to the causes of the Wars of the Roses in a manner that illustrates issues in context? One method could be as follows…

A Harvest of Heads

- What does this title suggest to students?

- Assuming they refer to beheadings, What would a ‘Harvest’ of heads mean?

- Why might a ruler choose to undertake such a task?

- Is this a sign of a strong ruler, or a weak ruler?

This opens up a lot of potential for discussion. Students will hopefully realise that heads relate to executions. That a harvest implies a lot of executions. So firstly, why were so many executions needed? And secondly, is such a response likely to have positive or negative consequences for the monarch and ruling classes? i.e. is it contextually appropriate justice being meted out?

Through simply looking at one term, students now have the potential to tackle things in a context driven manner.

What was the Harvest of Heads?

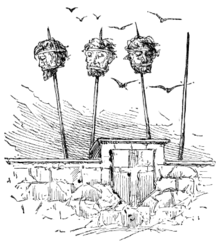

The Harvest of Heads is a name given by the people of Kent to the manner in which Jack Cade’s Revolt was put down. From Gregory’s Chronicle:

. . . On Candlemas Day, the king was at Canterbury, and with him was the Duke of Exeter, the Duke of Somerset, my lord of Shrewsbury, with many other lords and many justices. And there they held the Sessions four days, and there were condemned many of the Captain’s men for their rising, and for their talking against the king . . . And the condemned men were drawn, hanged, and quartered, but they were pardoned to be buried, both the quarters of their bodies and their heads withal.

And at Rochester nine men were beheaded at the same time and their heads were sent unto London by the king’s commandment, and set upon London Bridge all at one time; and twelve heads at another time were brought unto London and set up under the same form as it was commanded by the king. Men call it in Kent the harvest of heads.

Questions:

- Men were condemned for ‘their talking against the king.’ What does this tell you about medieval attitudes towards kings?

- For what types of crime was the punishment of ‘drawn, hanged and quartered’reserved?

- What is the meaning and significance of an executed person then being ‘pardoned to be buried, both the quarters of their bodies and their heads withal’?

- Why would the heads of beheaded men be sent from Rochester to be ‘set upon London Bridge all at one time’?

- Men call it in Kent ‘the harvest of heads’. What message had the King and his justices sent out to the people of Kent?

Why had there been a rebellion and what does that tell us about the causes of the Wars of the Roses?

Cade’s Rebellion is a very good route into exploring the causes of the Wars of the Roses. It brings in issues such as general lawlessness; failings in France; taxation; Foreign Trade; charges of maladministration; the notion of loyal opposition and can be linked to the factionalism that was increasingly apparent in court and government.

Sources on Cade’s Rebellion

Source 1: Gregory’s Chronicle, contemporary

The rebellion was a carefully organised rising of the people against the oppression and tyranny of Henry Vl’s ministers and particularly the Lord Treasurer, in their exaction of laws and taxes at the bitter end of the French Wars, a time of economic depression and poverty for the common people. What makes it significant is that even the local gentry followed Cade’s standard, and (from Stow’s Chronicle) it seems that the King’s followers, too, plainly suggested that, unless his traitorous ministers were dealt with, they would desert to the Captain. Cade led the rebels to Blackheath, retreated after a week, defeated part of the royal army at Sevenoaks (8 June) and took possession of London. Lord Saye, the King’s Treasurer, was executed; but the commons were soon driven out (5-6 July) and eventually dispersed, though Cade continued to resist till killed on 12 July. William Gregory (d. 1467) was Lord Mayor of London for 1451-2.

Source 2, from contemporary records.

PROCLAMATION MADE BY JACK CADE, “CAPTAIN OF YE REBELS IN KENT”

These being the points, causes and mischief’s of gathering and assembling of us the King’s liege men of Kent, the 3rd day of June, the year of our Lord 1450, the reign of our sovereign lord the king XXIX, the which we trust to Almighty God to remedy, with the help and the grace of God and of our sovereign lord the king, and the poor commons of England, and else we shall die therefore.We, considering that the king our sovereign lord, by the insatiable, covetous, malicious pomps, and false and of nought brought-up certain persons, and daily and nightly is about his Highness, and daily inform him that good is evil and evil is good . . .

Item, they say that our sovereign lord is above his laws to his pleasure, and he may make it and break it as him list, without any distinction. The contrary is true, and else he should not have sworn to keep it, the which we conceived for the highest point of treason that any subject may do to make his prince run in perjury . . .Item, they say that the commons of England would first destroy the king’s friends and afterwards himself . . .

Item, they say that the king should live upon his commons, and that their bodies and goods be the king’s; the contrary is true, for then needeth he never Parliament to sit to ask good of his commons . . .

Item, it is to be remedied that the false traitors will suffer no man to come to the king’s presence for no cause without bribes where none ought to be had, nor no bribery about the king’s person, but that any man might have his coming to him to ask him grace or judgement in such case as the king may give . . .

Item, the false lords impeach men to get their property . . .

Item, the law serveth of nought else in these days but for to do wrong, for nothing is sped almost but false matters for colour of the law for mede, drede and favour, and so no remedy is had in the court of conscience in any wise . . .

Item, we will that all men know that we blame not all the lords, nor all those that are about the king’s person, nor all gentlemen nor yeomen, nor all men of law, nor all priests, but all such as may be found guilty by just and true enquiry and by the law.

Item, we will that it be known that we will not rob, nor reve, nor steal, but that these faults be amended, and then we will go home; whereforewe exhort all the king’s true liegemen to help us, to support us . .

Item, we desire that all the extortioners might be laid down . . .

Item, taking of wheat and other grains, beef, mutton, and other victual, the which is importable hurt to the commons, without provision of our sovereign lord and his true council, for his commons may no longer bear it.

Item, the Statute upon Labourers, and the great extortioners of Kent, that is to say, Slegge, Crowmer, Isle and Robert Est.

Item, we move and desire that some true justice with certain true lords and knights may be sent into Kent for to enquire of all such traitors and bribers, and that the Justice may do upon them true judgement, whatsomever they be . . .

Item, to sit upon this enquiry we refuse no judge except four chief judges, the which be false to believe.

. . . The Lords followers went together and said, but the king would do execution on such traitors as were named, else they would turn to the captain of Kent.

Questions:

- Using source 1, list 5 causes of the uprising of 1450.

- Do items from Jack Cade’s proclamation (source 2) support the claims in source 1? Note where items support Gregory’s assessment.

- Who is Jack Cade most angered by? Use evidence from the sources to identify these people.

- How are the causes of the uprising connected? This may require an element of further reading.

Teacher Note: should you wish to explore ways of teaching about the Provenance of sources from the Wars of the Roses we recommend the Historical Association’s A-Level Guide. The ideas within that guide may influence your choice of questioning in our following discussion points. Also, see our guide to evaluating historical sources.

Discussion points

- What do the sources tell us about 15th-century society?

- What are the limitations of the sources?

- What problems might you expect historians of this period to face?

The causes of the uprising

These sources make the grievances fairly clear. Source 1 notes the “time of economic depression and poverty for the common people”. This was a period of unemployment and low wages in the South East. These are issues that affect communities: Who would be blamed for such problems? Are complaints based on fair reasoning?

There was a bitter end to the French Wars. So, is anyone to blame for that? The king has poor advisors: who, and is that accusation fair? Are there any in government whom the commons did not think were poor Lords?

The economy was struggling: why? what could be done to improve it? Is anybody in particular at fault?

Taxation was seen to be unjust: what was the system of taxation at the time? What would people consider to be fair and just taxation?

Inferences to be made

If the people of a large part of southern England, including some men of standing, were willing to participate in a revolt, then something clearly was going wrong. This is no distant revolt, it is in Kent, in the area of England through which news, trade, troops, passes. In simple terms: these people knew what was going on in society as well as anybody would. Similarly, any tension in the area would have been known about by the Royal authorities at a very early stage. So, why wasn’t it nipped in the bud? Why were grievances not tackled at an early stage? Why were leaders of the uprising not dealt with as they became rabble-rousers, instead of after the revolt had swollen in size?

Discuss these points with your class. It can act as an introduction into future work, or reading, on the causes of the Wars of the Roses.

Links

Causes of the Wars of the Roses

Personalities of the Wars of the Roses